To make use of an RSS feed, you need some "feed reader" (or "aggregator") software. Most modern web browsers have feed readers built in.

The RSS feeds for The Westmorland Orchestra are listed below...

The Westmorland Orchestra upcoming events:

https://www.westmorlandorchestra.org.uk/dbaction.php?action=rss&dbase=events

The Westmorland Orchestra news:

https://www.westmorlandorchestra.org.uk/dbaction.php?action=rss&dbase=uploads

Past Performances

Spring Concert

.jpg) Once again, Kendal Parish church was the venue for the Westmorland Spring Concert. That the orchestra is capable of delivering large scale works was demonstrated yet again on Saturday, March 29, when the players rose to the challenge of performing three well-known works, all standard repertoire pieces, but demanding works for any orchestra, amateur or professional.

Once again, Kendal Parish church was the venue for the Westmorland Spring Concert. That the orchestra is capable of delivering large scale works was demonstrated yet again on Saturday, March 29, when the players rose to the challenge of performing three well-known works, all standard repertoire pieces, but demanding works for any orchestra, amateur or professional.

Weber’s colourful and dramatic Overture: Der Freischutz, opened the programme. There was some impressive playing from the horns and woodwind section, ably supported by the strings and brass. The number of string players on stage was impressive and the their sound was strong and confident.

The young violinist Leora Cohen then joined the orchestra for Sibelius’ Violin Concerto. She is a most impressive player with a fine technique, fully able to cope with all the difficult passage work which is such a feature of this concerto. She was clearly in control, and was firmly supported by the orchestra under the careful guidance of conductor, Melvin Tay.After the interval came Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6. The strengths of the orchestra were revealed in this performance: a full, rich string sound; many expressive woodwind solos and a confident brass and percussion section. There were times when the brass overwhelmed the strings; perhaps more restraint is needed when performing in the Parish Church as the boomy acoustic tends to magnify the brass sound.

This was a well planned programme giving each section of the orchestra an opportunity to show their capabilities. The orchestra clearly enjoys a good relationship with Melvin Tay and the success of this concert was due to his clear direction and players’ response. It was good to see the concert so well supported on this occasion. Let us hope that this will continue as the Orchestra begins to prepare for the next concert in June.Christmas Concert

The Christmas concert on December 8 was a very jolly affair. In a programme partly aimed at children, it was good to see so many of them in the audience. Some may have been overwhelmed by the length of the programme but most made it to the end to provide extra percussion (jingle bells) in Leroy Anderson’s, famous Sleigh Ride played by the orchestra as an extra item at the end of the concert.

The Christmas concert on December 8 was a very jolly affair. In a programme partly aimed at children, it was good to see so many of them in the audience. Some may have been overwhelmed by the length of the programme but most made it to the end to provide extra percussion (jingle bells) in Leroy Anderson’s, famous Sleigh Ride played by the orchestra as an extra item at the end of the concert.

Matthew Arnold’s colourful ‘Tam O’Shanter’ cannot fail to have aroused the attention of even the youngest members of the audience as they listened to the composer’s cheeky tunes and watched the various antics of the percussion department. Their battery of instruments brilliantly illustrated Arnold’s musical interpretation of Robert Burns’ entertaining poem describing the adventures of boozy Tam, and the chase across the moors on a wild night by the devilish witches.

In Ian Farrington’s ‘Scary Fairy Saves Christmas’, written to illustrate in music the series of poems written by Craig Charles, the narrator Matt Berry was suitably dramatic in his narration and the depiction of the text on the screen helped to get the story across. The players in the brass section let their hair down, clearly enjoying the chance to play in dance band style as they worked their way through in Farrington’s cleverly orchestrated score. The whole orchestra responded well to conductor Melvin Tay’s clear direction, not only in this piece but throughout the whole programme. The many tempo changes – always a potential point of disaster for an orchestra – were well-managed.

This Christmas programme was very different from what is to come later in the season and although the audience was not as large as the orchestra perhaps hoped for, it was a well-devised programme and gave much pleasure to young and old alike, demonstrating yet again the dedication and skills of so many local players.

Clive Walkley

Summer Concert

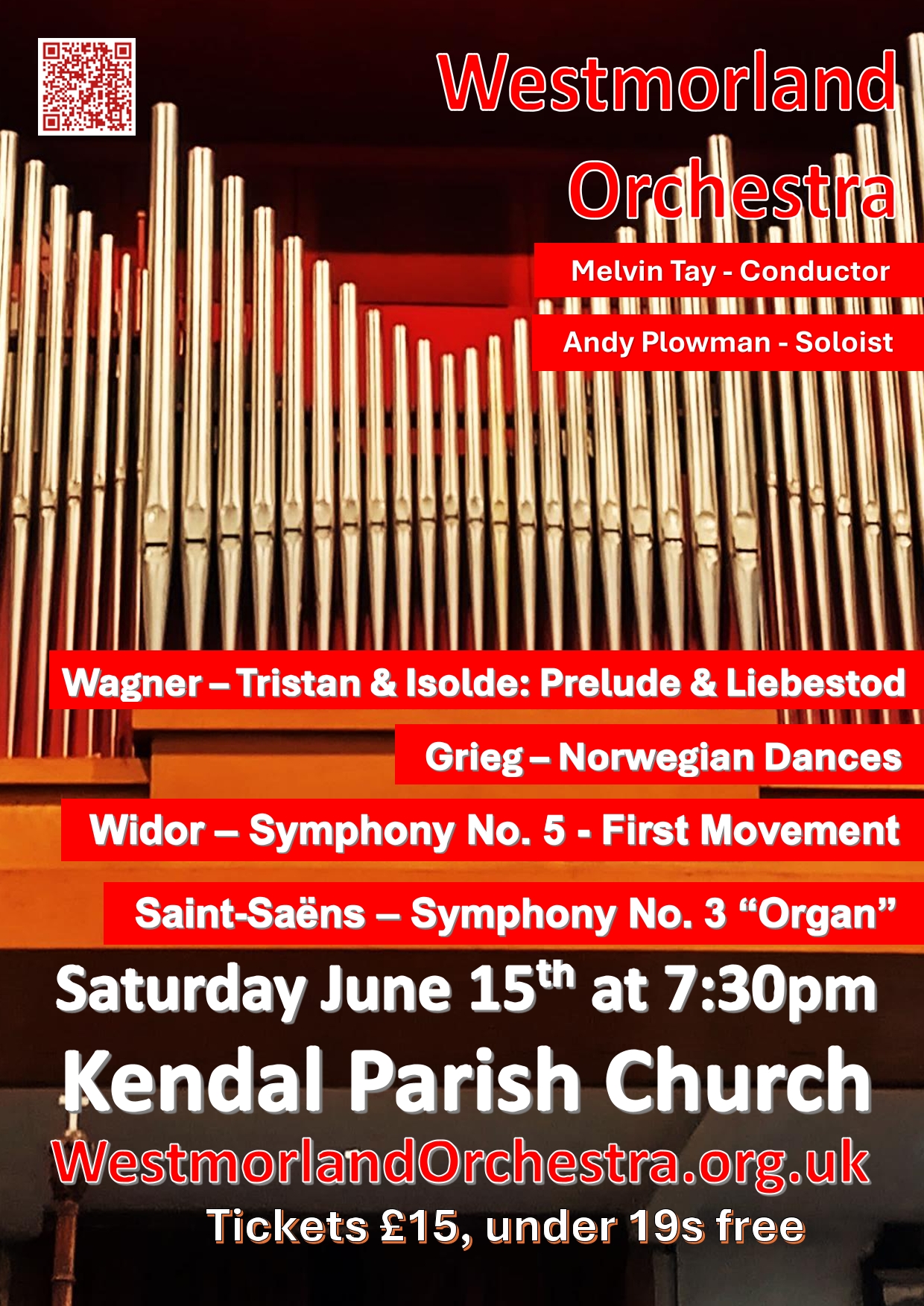

Ambitious programme planning seems to be a feature of the Westmorland Orchestra’s concerts these days. But the successful concert in Kendal Parish Church on Saturday June 15 proved that the orchestra can rise to the challenge of presenting large-scale works.

Ambitious programme planning seems to be a feature of the Westmorland Orchestra’s concerts these days. But the successful concert in Kendal Parish Church on Saturday June 15 proved that the orchestra can rise to the challenge of presenting large-scale works.

It was a brave move to open the concert with Wagner’s Prelude and Liebestod from his opera Tristan and Isolde. The opening movement is a nervous moment for cellos and woodwind but it came off. The large cello section produced a lovely cantabile line and the woodwind section responded expressively with well-shaped phrases. The huge climaxes of the Liebestod were very effective with the brass section making a significant contribution – not forgetting, too, the important harp arpeggios. This is a passionate piece of orchestral writing and the performance was entirely convincing, releasing all the pent up emotions that Wagner must have felt when he wrote the work.

It was good to hear all four of Grieg’s Norwegian Dances; no. 3 with its jaunty tune is the one usually favoured in concerts. The final Allegro molto peasant dance brought the first half of the concert to a successful conclusion.

How fortunate Kendal Parish Church is to have such a fine organist as Andy Plowman. His playing of the first movement of Widor’s Symphony No.5 for organ was masterly. Audience enjoyment of this piece was enhanced by video shots of Andy at work.

Kendal Parish Church was the obvious venue for this concert. With a programme requiring an organ as part of a large orchestra there was no other concert venue in Kendal with the necessary space to allow us to hear Saint-Saëns’ ‘Organ’ Symphony in all its glory. The climax of this work, of course, is the point in the last movement when the organ comes crashing in and, in spite of the organ being positioned at the other end of the church far from orchestra and conductor, modern technology ensured that this treasured moment was achieved effectively. The whole church was filled with sound which brought an instant and well-deserved response from the audience when the final chord was reached.

In spite of the rather boomy acoustic (and uncomfortable pews!) the Parish Church proved a good venue for this programme, all so ably directed by conductor Melvin Tay who must have been immensely proud of what he had achieved.

We look forward to more concerts by the talented and dedicated players who, week by week, give up their time to prepare large orchestral works for the benefit of residents of South Lakeland.

Clive Walkley

Spring Concert

Well done to the orchestra for presenting such an enterprising programme on Saturday March 23! It was good to hear works that have not been presented in Kendal before – at least not in recent years. The great strength of this programme was the inclusion of Vaughan Williams’ colourful ‘London Symphony’ as the major work. Usually, if we want to hear a major symphony by Vaughan Williams, we have travel much further afield; it was a delight to have a chance to hear this lovely work performed on our door step.

The concert got off to a confident start as violas, cellos and double bass plunged down to the depths for the sombre opening of Berlioz’ King Lear Overture. This is not one of Berlioz’s most popular overtures. It does not have the same appeal, for example, as the later overtures, Le Corsaire or Le Carnaval romain. Listening to it, one can see why: it seems to rely heavily on its brilliant orchestration to make an effect, and possibly on lengthy programme notes for an audience to fully appreciate it. If the orchestra had adopted a faster speed for the allegro section, it might have come alive more; as it was, it seemed a little lack lustre, although the brass section was impressive at points of climax.

Horn soloist, Angela Barnes, gave a fine performance of Strauss’ Horn Concerto No. 2. This is an extremely challenging work for both soloist and orchestra with little respite for the soloist until the slow movement. Bringing a performance together on just two rehearsals – soloist and orchestra – is a huge challenge and all credit to conductor and players for achieving this.

It was clear that much preparation had gone into the London Symphony. Its a long work requiring stamina and concentration but the orchestra rose to the challenge and there were many arresting moments. Woodwinds and horns have a big part to play in setting the mood and character of this journey through Edwardian London and there was some lovely playing, particularly in the slow movement and Scherzo, the latter requiring great agility on behalf of the bassoons; the horns, too, excelled themselves. Perhaps the brass were a little too strong at times but this did not detract from the overall performance. Conductor, Melvin Tay, steered the orchestra firmly through the work adopting sensible speeds for the faster sections.

One of the most impressive moments in the performance was the quiet Epilogue in the last movement. The work ends with one long quiet note deep down on cellos and double basses. This vanished into nothing, as Vaughan Williams intended, and this final moment was greeted in stunned silence before enthusiastic applause rounded of the evening.

This was a concert that should have been attended by far more people than it was. Let us hope that the orchestra’s next concert in Kendal Parish Church in June will draw in a bigger crowd. The orchestra is certainly worthy of greater support.

Clive Walkley

Summer Concert

-page-0.jpg)

Borodin: Prince Igor Overture

Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto No. 2

Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 2

Conductor: Martin Budgett

Soloist: Dominic Degavino

A large audience assembled in the generous spaces of Kendal Parish Church to enjoy a concert of Russian music under the baton of guest conductor Martin Budgett. I felt that the acoustics were warmer than those in the Leisure Centre, the usual venue, and this helped the various sections of the orchestra to blend together perfectly and the violins to hold their own against the rest. The hot weather provided a challenge for the orchestra to keep their instruments tuned, one which they overcame successfully. The pillars made for poor sight-lines for some people, although two large screens were provided in compensation.

The concert opened with Alexander Borodin's overture for his opera Prince Igor. This was left unfinished at his death in 1887, like many of his works, and was completed by his friend Glazunov, partly from his memory of hearing the piano version. Vigorous conducting and well-executed brass calls and horn and woodwind solos complemented excellent tone from the strings.

Rising star of the concert platform Dominic Degavino was the soloist in Rachmaninoff's 2nd Piano Concerto, and I cannot remember hearing it played more beautifully. Despite its familiarity, the work is technically very demanding and a real feat of memory. Rachmaninoff suffered from depression and 'writer's block' on and off throughout his life, often brought on by scathing (and unjustified) critical reviews. His second piano concerto, finished in 1901, was an unqualified success, however, and has remained popular ever since.

From the portentous opening chords we knew we were in for a real treat of virtuosity, coupled with sensitive and emotional melodic lines. The orchestra blended well with the piano, only dominating once or twice, and providing clear woodwind solos on the (rare) occasions when the piano was silent. The sublime second movement was very moving and the brilliant finale was an exhilarating conclusion to a totally mesmerising performance, loudly acclaimed by audience and orchestra alike.

After such a feast of music, the second half, consisting of Tchaikovsky's 2nd Symphony, could have been something of an anti-climax, but Martin Budgett drew excellent and exciting playing from the orchestra, who clearly like working with him. Tchaikovsky was already a popular composer when he wrote his second symphony, in which he aimed to introduce folk tunes into the symphonic structure, but with limited success, which caused him to revise the work significantly. Some of the melodies are from Ukraine (then known as Little Russia), where Tchaikovsky spent his summers, and the symphony at one time was nicknamed the 'Ukrainian' rather than its usual name of 'Little Russian'.

The players carried off the demanding opening horn and bassoon solos perfectly, with powerful string tone subsequently. The complex rhythms and repeats in the third movement were crisp, with fine woodwind playing; the finale begins with a chorale followed by a folk tune which is elaborated and then followed by a lyrical second subject in the violins. One of Tchaikovsky's characteristically exciting endings including timpani, cymbals, bass drum and tam-tam was a fitting conclusion to a very fine concert.

Phil Johnstone

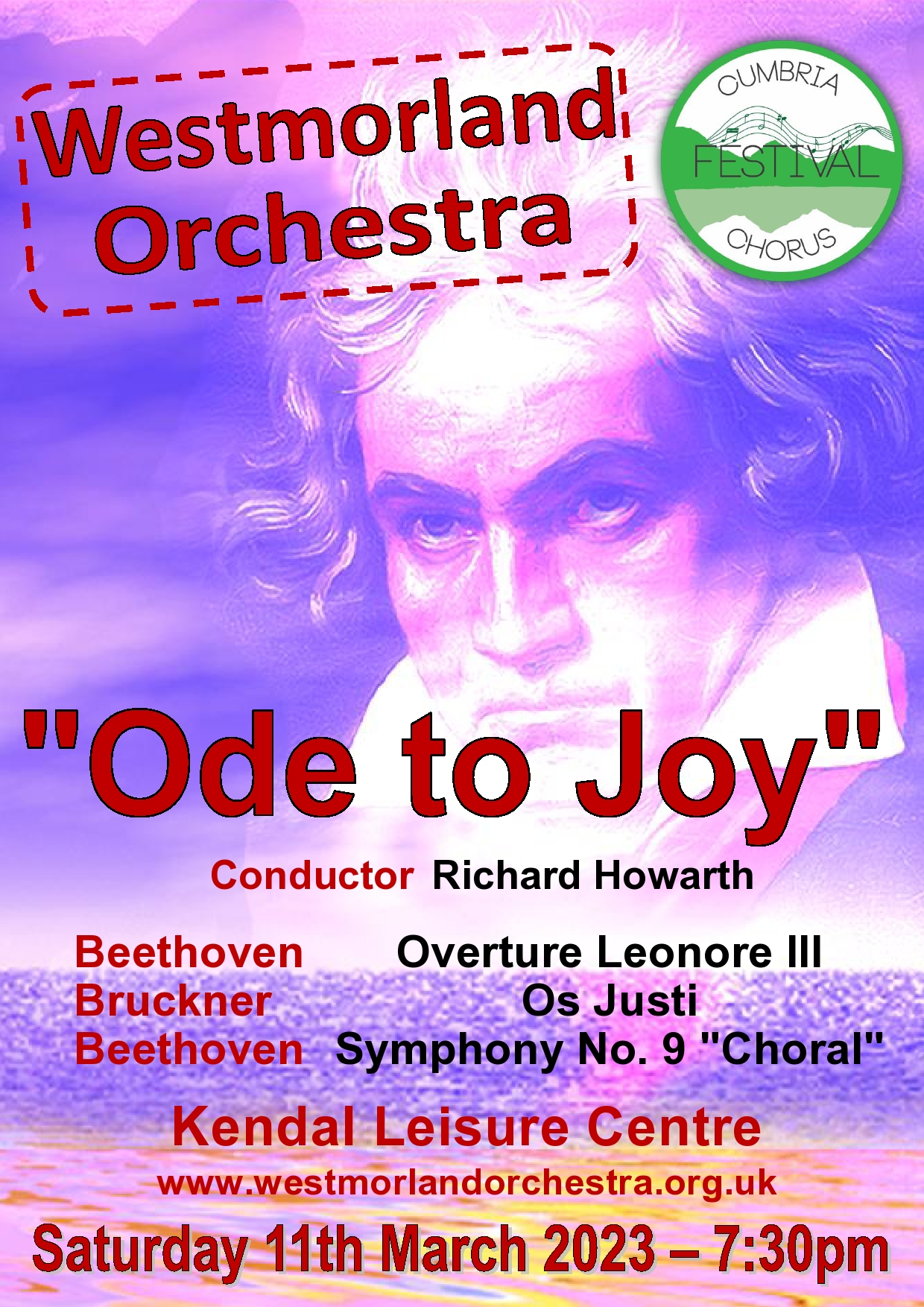

Beethoven 9th “Ode to Joy”

Cumbria Festival Chorus – Chorus Master: Ian Jones

Soprano: Sarah Fox

Mezzo-soprano: Kathryn Rudge

Tenor: Andrew Tortise

Bass-baritone: Samuel Snowden

Westmorland Orchestra Concert - Westmorland Hall, Kendal Leisure Centre

This opening concert in the Mary Wakefield Westmorland Music Festival 2023 was also the last in Richard Howarth's tenure as Music Director and Conductor of the Westmorland Orchestra. A nearly full house, despite the wintry weather, saw the orchestra joined by the Cumbria Festival Chorus and their Chorus Master Ian Jones. The orchestra began with Leonore III, the third and most popular overture which Beethoven wrote for his only opera Fidelio, and which provides a summary of the opera and its best melodies. From its sombre start with hushed strings through the offstage trumpet calls to the blazing final bars, the orchestra got into its stride under Richard Howarth's crisp direction.

Bruckner, better known for his nine symphonies, also wrote many settings of sacred texts for unaccompanied choir. Os Justi, with words from Psalm 37, gave the chorus a chance to demonstrate their wonderfully balanced and controlled sound, at once motional and devout.

After the interval we were treated to a fiery and powerful performance of Beethoven's Choral Symphony, one of the pinnacles of music and all the more remarkable for being completed when he was totally deaf. The first movement with its fragmentary themes and complex development is hard to carry off convincingly, but the orchestra rose to the occasion with pure woodwind lines, and the cellos and basses particularly striking. The leader, Pamela Redman, carried on valiantly on another violin despite breaking a string early on.

The scherzo-like second movement was taken at a steady pace to let every note sound. The timpani, used extensively throughout this symphony, were always crisp and perfectly accented – a pity that it was hard to see the performer! The woodwind were clear and the brass restrained and sonorous.

The slow third movement, in my opinion one of the most beautiful pieces ever written, had lush sound and perfect tempi, although sometimes it was hard to hear the first violins' ornamentation over the rest of the orchestra – perhaps the fault of the hall's acoustics.

In the fourth and mightiest movement, Beethoven introduced voices into the classical symphony for the first time. His writing makes little concession to the human voice, but the well-drilled chorus and four soloists accepted the challenge magnificently. The opening recitatives on cellos and basses were powerful and the hushed introduction of the ‘Ode to Joy' theme was enhanced by beautiful tone from the viola section. After the orchestral peroration, the baritone soloist introduced the choral setting of Schiller's poem. Richard Howarth paced the variations perfectly and drew crisp and energetic playing from the orchestra. The chorus and soloists put their hearts and souls into the words, although at times it was hard to hear any except the soprano – I feel that the soloists would have been better placed at the front of the stage.

As the symphony moved to its tremendous life-affirming conclusion, audience and performers alike were caught up the joyful excitement, and the enthusiastic, well-merited applause proved that this concert was a fitting climax to Richard Howarth's work with the Westmorland Orchestra.

Phil Johnstone

Northern Lights

This concert, part of Richard Howarth’s last season as Musical Director of the orchestra, was entitled ‘Northern Lights’ and contained three pieces by Scandinavian composers evoking the natural world. The temperature of the hall also helped to establish the Nordic atmosphere!

This concert, part of Richard Howarth’s last season as Musical Director of the orchestra, was entitled ‘Northern Lights’ and contained three pieces by Scandinavian composers evoking the natural world. The temperature of the hall also helped to establish the Nordic atmosphere!

The orchestra rose to the challenge of the works superbly. The first, Carl Nielsen’s overture ‘Helios’, begins quietly with cellos and basses to which are added horn calls. It portrays the rising and noon brilliance of the sun, in a powerful climax, before sinking into a peaceful sunset, all in Nielsen’s characteristically chromatic yet approachable style. The trumpets and trombones were crisp and not over-dominant, the horns confident, the woodwind excellent as usual, and the strings well-drilled, although the violins, as in most amateur ensembles, would benefit from increased numbers in the louder sections.

The second work, ‘Cantus Arcticus’ by the Finnish composer Einojuhani Rautavaara, takes inspiration from the landscapes and birdsong of the north – in fact an essential part of the piece is a recording of wetland birds, a shorelark, and whooper swans, which plays almost the whole time and is embroidered upon by the orchestra in an impressionistic manner. The opening movement makes big demands on the woodwinds, who accepted the challenge magnificently. The conductor steered the players through the shifting rhythms and long crescendos and diminuendos, and carefully blended the various sections of the orchestra into a seamless whole. The strings in particularly showed their rich tone. I for one felt transported to the Arctic landscape.

After the interval, the concert concluded with Jean Sibelius’s 1st Symphony, which helped to establish him as a first-rank composer. Richard Howarth drew the best from all the players, expertly managing the many changes of tempo and mood, and allowing each section to be heard to advantage even in the surging fortissimo passages. The exposed clarinet solo which begins the work, and the complex timpani part in the third movement, were handled faultlessly. The string tone was lush and the brass restrained but powerful when required. I had the impression throughout that the orchestra were enjoying themselves.

The audience was somewhat reduced for this afternoon concert, perhaps by the lure of Christmas shopping, but those that did attend were treated to a feast of excellent music.

Phil JohnstoneSpring Concert

It was pleasing to see a near capacity audience at the Westmorland Orchestra’s recent concert in the Victoria Hall, Grange-over-Sands. On a damp evening and with the ever- growing threat of the coronavirus, the orchestra must have been heartened to be welcomed by such a large gathering. The downside of the move from the orchestra’s usual venue, Kendal’s Westmorland Hall, to a much smaller hall, however, was the less than ideal acoustic for an orchestra of 50 plus players. The sound from the wind department (brass especially) was overwhelming at times and did have an adverse impact on the performance. That said, there was much to admire in the playing of the three fine works on the programme.

The concert opened with the Overture and selected movements from Beethoven’s music for the ballet ‘The Creatures of Prometheus’. This got off to a confident start and immediately it was obvious that the orchestra had been well prepared for the performance. The strings deftly negotiated their rapid passage work and the woodwinds demonstrated a lightness of touch in their solo passages. The demanding duet for basset horn and oboe was confidently delivered by sectional principals, Ruth Watton and Nigel Atkinson.

The young Singaporean pianist, and multiple prize winner, Serene Koh was the soloist in Mozart’s C minor Piano Concerto K491. Martin Roscoe, the Westmorland Orchestra’s President, described her as ‘an ideal soloist’ for this concerto, and so it turned out. Her playing had the clarity which Mozart’s music demands. She produced a beautiful tone in the many quiet solos passages with immaculate phrasing and beautifully sustained legato lines. Her dazzling technique enabled her to negotiate Mozart’s rapid passage work, including the difficult cadenza, with ease. Sadly, the work’s opening was marred by some uncertain intonation in the strings and wind and throughout one was aware ofthe heavy bass line of the orchestra’s eight cellos and four double basses.

After the interval came Mendelssohn’s ‘Italian’ Symphony. This produced some of the best playing of the evening. The performance had energy and conductor, Richard Howarth, drove on the outer movements with great momentum, never allowing the tempo to flag. There was a good balance in the Andante movement between the woodwind hymn-like melodic line and string marching accompaniment. In the third movement the two horn players distinguished themselves in their horn calls with more impressive playing from the woodwind section. The final exhilarating Saltarello proved a fitting end to a concert which must have brought cheer to many.

Clive WalkleyMay Concert

The Westmorland Orchestra’s latest concert got off to a fine start as the whole orchestra launched into Schubert’s tuneful sixth symphony: what better way to start a concert than with everyone joining in the two loud chords which open this work – a great confidence booster! The confident opening was a sign of things to come. So much of this symphony is dominated by Schubert’s lovely woodwind writing and here the Westmorland’s woodwind section excelled. The flutes in particular have an important role and their playing sparkled throughout the work; they were ably backed up by their colleagues. Conductor, Richard Howarth, paced the work at a safe speed which resulted in a very satisfying and enjoyable performance. Although not one of Schubert’s most difficult symphonies, the work is not without its challenges but is not beyond the capabilities of a good amateur orchestra like the Westmorland.

Following the Schubert, Lily Whitehurst was the violin soloist in Max Bruch’s Romance in A, Op. 42. Lily is in her final year as an advanced student at the Royal Northern College of Music where she has won many awards. She is no stranger on the professional orchestral scene and has recently been appointed to a place in the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra. Her playing is beautifully lyrical. Occasionally she was overwhelmed by the orchestra but overall this did not diminish the quality of the performance.After the Bruch she showed another side to her artistic personality as she romped effortlessly through Manuel de Falla’s rhythmically exciting Spanish Dance. The clicking of the castanets brought the necessary Spanish quality to the performance, bringing the first half of the concert to a very satisfying close.

After the interval, we heard Brahms lengthy first Serenade for orchestra, written when he was still a relatively unknown composer. The work is in six movements and contains many hallmarks of his later, mature style. But it is thickly scored in places and there were times when the strings were overwhelmed by the wind department. This is not necessarily a criticism of the string section; the players produced a good firm sound, but Brahms’ orchestral music demands weight in this section. Again the wind players excelled themselves, particularly in the fifth movement when they came into prominence. I’m sure the orchestra would welcome the addition of more string players to swell the ranks!Sadly, there were many empty seats in the hall and the enthusiasm and skill of the players, many of whom travel long distances to be part of the orchestra, deserve much better support.

Clive Walkley